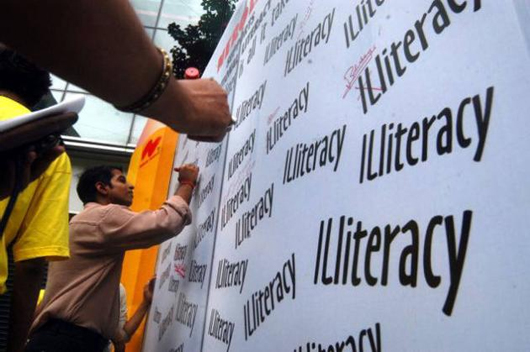

United Nations, Jan 29: India has by far the largest population of illiterate adults at 287 million, amounting to 37 per cent of the global total, a United Nations report said highlighting the huge disparities existing in education levels of the country's rich and poor.

The 2013/14 Education for All Global Monitoring Report said India's literacy rate rose from 48 per cent in 1991 to 63 per cent in 2006, the latest year it has available data, but population growth cancelled the gains so there was no change in the number of illiterate adults.

India has the highest population of illiterate adults at 287 million, the report published by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation said.

The report further said that the richest young women in India have already achieved universal literacy but the poorest are projected to only do so around 2080, noting that huge disparities within India point to a failure to target support adequately towards those who need it the most.

"Post-2015 goals need to include a commitment to make sure the most disadvantaged groups achieve benchmarks set for goals. Failure to do so could mean that measurement of progress continues to mask the fact that the advantaged benefit the most," the report added.

The report said that a global learning crisis is costing governments USD 129 billion a year. Ten countries account for 557 million, or 72 per cent, of the global population of illiterate adults.

Ten per cent of global spending on primary education is being lost on poor quality education that is failing to ensure that children learn.

This situation leaves one in four young people in poor countries unable to read a single sentence.

In one of India's wealthier states, Kerala, education spending per pupil was about USD 685.

In rural India, there are wide disparities between richer and poorer states, but even within richer states, the poorest girls perform at much lower levels in mathematics.

In the wealthier states of Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, most rural children reached grade 5 in 2012.

However, only 44 per cent of these children in the grade 5 age group in Maharashtra and 53 per cent in Tamil Nadu could perform a two-digit subtraction.

Among rich, rural children in these states, girls performed better than boys, with around two out of three girls able to do the calculations.

Despite Maharashtra's relative wealth, poor, rural girls there performed only slightly better than their counterparts in the poorer state of Madhya Pradesh.

The report said widespread poverty in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh affects the chance of staying in school until grade 5.

In Uttar Pradesh, 70 per cent of poor children make it to grade 5 while almost all children from rich households are able to do so.

Similarly, in Madhya Pradesh, 85 per cent of poor children reach grade 5, compared with 96 per cent of rich children.

Once in school, poor girls have a lower chance of learning the basics. No more than one in five poor girls in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh are able to do basic mathematics.

The report added that children who learn less are more likely to leave school early.

In India, children who achieved lower scores in mathematics at age 12 were more than twice as likely to drop out by age 15 than those who performed better.

In some countries, the engagement of teacher unions has improved policies aimed at helping disadvantaged groups. In India, teacher unions have a major influence on state legislatures and governments.

If days are lost because teachers are absent or devote more attention to private tuition than classroom teaching, the learning of the poorest children can be harmed.

Across India, absenteeism varied from 15 per cent in Maharashtra and 17 per cent in Gujarat – two richer states – to 38 per cent in Bihar and 42 per ccent in Jharkhand, two of the poorest states.

There is much evidence of the harm done to students’ learning because of teacher absenteeism.

In India, for example, a 10 per cent increase in teacher absence was associated with 1.8 per cent lower student attendance.

Governments should work more closely with teacher unions and teachers to formulate policies and adopt codes of conduct to tackle unprofessional behaviour such as persistent absenteeism and gender-based violence.

It said codes of practice should be consistent with legal frameworks for child rights and protection and a range of penalties, such as suspension and interdiction, clearly stipulated.

Policy-makers should ensure the curriculum focuses on securing strong foundation skills for all, is delivered at an appropriate pace and in a language children understand.

"India's curriculum, which outpaces what pupils can realistically learn and achieve in the time given, is a factor in widening learning gaps."

Comments

Add new comment